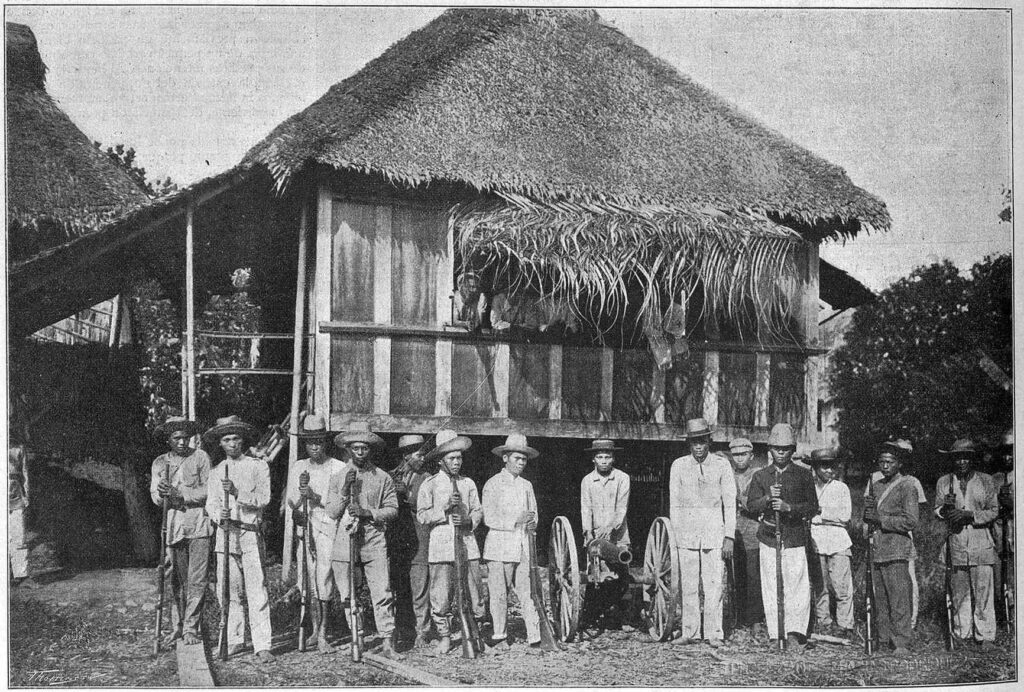

The Little Brown Brother “Shoots” Back:

Postcolonialism in Filipino Cinema at the Turn of the Century, 2000-2010

ABSTRACT: Throughout most of the 20th century, the dominance of Hollywood hindered the development of a distinct film identity and tradition within Philippine cinema. However, from this seemingly uninspiring state, a vibrant independent film community emerged and thrived during the first decade of the 21st century. This transformation was made possible by the introduction of more accessible digital video cameras in the 1990s. The digital medium provided independent filmmakers with the opportunity to explore various storytelling approaches centered around Philippine realities, which resonated with younger audiences. This paper posits that Filipino independent, or “indie,” cinema experienced a surge in creativity during the first decade of the 21st century and established what I refer to as a “postcolonial aesthetic” to counter the dominance of the Hollywood cinematic structure. I draw upon the ideas of Renato Constantino and Bienvenido Lumbera as my primary framework to trace the trajectory of independent and mainstream Filipino cinema during this period. Through an examination of two films from that era—one independent (Ded na si Lolo [Grandpa is Dead], 2009) and one mainstream (Baler, 2008)—I argue that Philippine cinema truly came into its own between 2000 and 2010, and its unique characteristics continue to influence the post-Covid era. Keywords: Cultural imperialism, American hegemony, Philippine cinema, period movies, independent films The movie industry is both a victim and an ally of American cultural aggression. It is a victim precisely because it is an ally of Hollywood, not by conscious design but by the conditioning effect of decades of exposure to Hollywood movies. At the same time, it is an ally in the sense that the Hollywood model is pervasively the frame of reference […] Hence, the movie industry is a reflection of Philippine society for it is the clearest and simplest depiction of the neo-colonial situation. – Renato Constantino (1977, p. 131) In just a few sentences, Renato Constantino was able to accurately describe the state of the Philippine movie industry of his time. American cultural imperialism has reduced the industry to a caricature of Hollywood. If Hollywood had Charlie Chaplin, we Filipinos had Canuplin, a vaudeville comedian whose appearance and gestures resembled Chaplin. If James Bond/Agent 007 is an international super spy (and unremitting ladies’ man) of the British government, Filipino movies used to have Tony Falcon/Agent X44, also a super spy (sans the “international” label but an unremitting ladies’ man nonetheless) with thick sideburns as his trademark. In the age of the Hollywood blockbusters in the 1980s as exemplified by Ghostbusters, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, and Dune (all released in 1984), Filipino comedy king Dolphy starred in a movie that referenced all three – Goat Buster: Sa Templo ni Dunê (Goat Buster: In the Temple of Dunê, 1985). Indeed, the specter of Hollywood movies since the beginning of the 20th century has stunted the development of a distinctly Filipino cinema, and the cinema that the Filipino movie industry conceived was a mere distortion or poor imitation of Hollywood. Lacking technological resources and skilled artisans, the movie industry simply did not have the means to be at par with the Hollywood films that it was trying to imitate; and in the absence of a clear artistic vision, movie producers simply resorted to doing mostly parodies and spoofs as film production was primarily regarded as a commercial venture intended to produce a quick profit. Therefore, despite the industry’s considerable output from the 1950s up to the 90s and the fact that movies were once known as the country’s “national pastime” (David 1990), only a handful of films today are hailed as cinematic gems. What we have in abundance are senseless flicks anywhere from Sabi Barok Lab Ko Dabiana (Barok Said I Love Dabiana, 1978) to Wrong Rangers (1984, a parody of the Lone Ranger film and television series) to movies with absolutely meaningless titles (e.g., Horsey-horsey Tigidig-tigidig, 1986; Haba-baba-doo! Puti-puti-poo!, 1998; Tiktaktoys: My Kolokotoys, 1999; Isprikitik: Walastik Kung Pumitik, 1999). Likewise in the 1990s, advancements in film technologies (e.g., the introduction of CGIs or computer-generated images) combined with America’s push for globalization paved the way for the spectacle cinema of Hollywood to systematically dominate all modes of cinematic imagery, production, and reception, resulting in a standardized film culture not just for the Philippines but for most of the world. Unable to keep up, the movie industry’s production declined. From an average of two hundred films annually in the 1970s and 80s, the output has gone down to an average of fifty per year since 2003 (Alberto, 2008, para. 3). However, at the onset of the twenty-first century, the Philippines saw a surge of independent, or “indie” films produced by a new generation of filmmakers. This was made possible by the introduction of the high-resolution digital video camera in the 1990s. The changing of format from celluloid film to digital video freed the independent filmmaker from the high costs of mainstream filmmaking and the commercial demands of the studios. It gave them the liberty to tackle more unusual or controversial subject matters and present new modes of storytelling. By 2005, indie cinema took center stage when two film festivals exclusively devoted to digital indie films were established – the Cinemalaya Independent Film Festival and the Cinema One Originals. In its first year alone, the hugely popular festivals produced now-classic indie films such as Auraeus Solito’s Ang Pagdadalaga ni Maximo Oliveros (The Blossoming of Maximo Oliveros), Doy del Mundo’s Pepot Artista (Pepot Superstar), Mario Cornejo and Monster Jimenez’s Big Time, and Jon Red’s Anak ng Tinapa (A Kipper’s Child). In 2009, indie filmmaking reached its peak when Brillante Mendoza became the first Filipino to win the Best Director award at the Cannes Film Festival for his unapologetically brutal film Kinatay (“The Execution of P”). Inspired by independent