Caring in Curating:

Curating Art, Spaces, and the Self

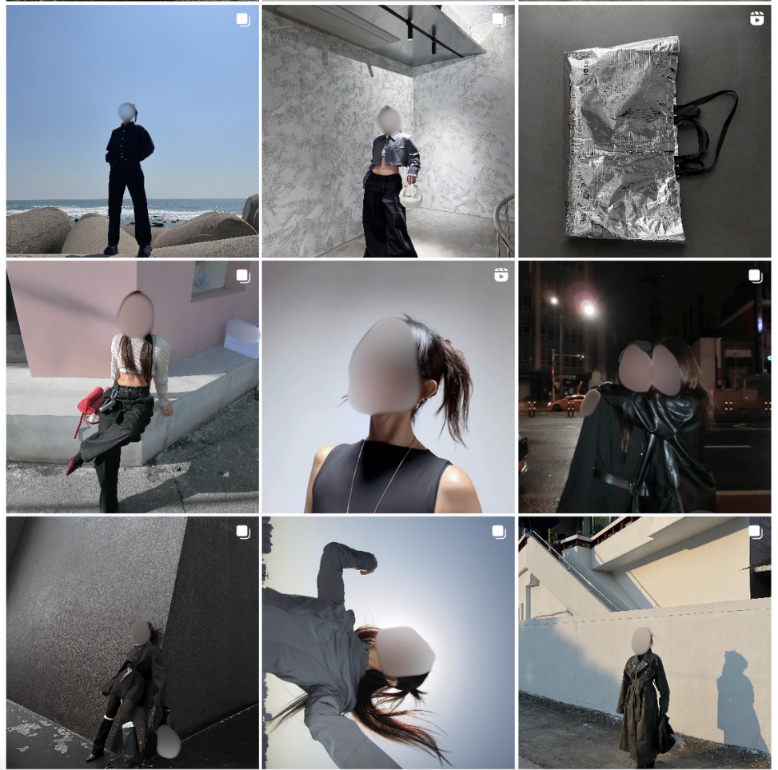

ABSTRACT: This paper explores how curation extends beyond the art world and is applied to various professional spheres like libraries, news production, and social media. My approach to historicizing the concept of curation is largely inspired by Van der Heijden’s concept of hybridization among media apparatuses. Rather than solely looking at the interrelation of media tools, I also looked into how the role of a curator transpires in offline and online spaces. Meanwhile, my understanding of curation is mainly drawn from Balzer’s (2014) book on curationism and Obrist’s (2008) discussions with other prominent figures in the art scene. My paper does not intend to discount the profession of a curator, but instead, I argue that users continuously embody the role of curators as they navigate and shape their external identities within the dynamic landscape of digital platforms. This paper posits that such practice not only involves users curating their online personas but also fuels the continued growth and influence of these platforms (Smythe, 1977). Keywords: curation, digital media, social media, audience commodity Every week, I receive a notification from my phone about my average screen time. For this week, my daily average was seven hours and nine minutes—with two hours of this spent scrolling through the bottomless pit of TikTok. This popular video-sharing app allows users to upload short-form videos of no more than 10 minutes. My friends mostly use the app to partake in the latest TikTok trends. However, as an introvert, I prefer to go incognito and mostly use TikTok as a search engine for food, travel destinations, and beauty must-haves. TikTok is widely known for providing a virtual space where one can be their authentic selves (Schellewald, 2023). It’s been two years since I created my TikTok account, and throughout this period, I’ve seen how fellow users leverage the platform to create feel-good content via dance challenges, tutorials, and thrift finds. Popular influencers, personalities, and, to a certain extent, A-list Hollywood stars have also used the platform to present themselves as someone relatable or ordinary who experiences the same joys and struggles as the rest of us. At that time, I found it refreshing to see users and friends deviate from the aspirational and picture-perfect life we once lived on Instagram. However, looking back now—and having the opportunity to look into publications about TikTok—it seems that the authenticity that we enjoy watching on TikTok is just as curated and performative as uploading a photo on Instagram or a vlog on YouTube (Barta et al., 2023). In scholarship, they attributed authenticity and relatability to what makes content on TikTok viral or popular among its users (Schellewald, 2023; Vizcaíno-Verdú & Abidin, 2022). This means that the videos that become famous on the platform are primarily determined by users who spend time watching and engaging with these videos. As a result, this becomes an invisible trigger for others who aspire to become famous on the platform, as they aim to create content that resonates with the platform’s users (Schellewald, 2023; Vizcaíno-Verdú & Abidin, 2022). This implies that, as users, we meticulously shape our online identities to align with the norms of each platform, thus assuming the role of curators for our online personas. I find it noteworthy that curation, a practice that has been historically and intricately linked with the organization of artwork in museums and galleries (Obrist, 2011), now extends to the curation of online personas on social media platforms alongside the prevalent documentation of our daily lives and milestones online. My position to delve into curation on blogs and social media stems from my professional experience in public relations and corporate communications. In these fields, curation was consistently done to garner public favor and bolster brand reputation via press releases, interviews, social media content, and publicity stunts. Meanwhile, my interest in looking into LookBook, Instagram, and TikTok is driven by professional and personal motivations. LookBook and Instagram were once recognized as one of the leading platforms (Ewens, 2021; Iqbal, 2024) and subsequently held significant influence over my fashion preferences during my collegiate years in an exclusive girls’ school. As for TikTok, its rapid rise in popularity intrigues me, despite concerns surrounding data privacy (Samaniego, 2023). I am interested in examining how curation practices unfold on TikTok, especially given the platform’s emphasis on authenticity. Recent statistics also indicate that Filipinos lead in video consumption with 50.7% and rank the highest in terms of watching vlogs or influencer videos each week (Tan, 2024). Ergo, the country’s rich usage of online platforms, armed with the Filipinos’ continuous dependence on mobile phones to access and consume information from the Internet(Diaz, 2024), provides a favorable ground to explore the interconnectedness of the curated self and audience commodification within these virtual spaces. Given these contexts, I argue that users continuously embody the role of curators as they navigate and shape their external identities within the dynamic landscape of digital platforms. This paper posits that such practice not only involves users curating their online personas but also fuels the continued growth and influence of these platforms. My paper is inspired mainly by Van der Heijden’s (2018) approach to historicizing media apparatuses based on hybridization. I illustrate how curation is applied in various professional spheres and online media. Meanwhile, my understanding of curation and its application outside the art world is mainly drawn from Balzer’s (2015) discussion on curationism. Although his book discusses the evolution of curated works over time (Balzer, 2015), I mainly apply the fundamental principles of curation in offline and online spaces like the library, blogs, and social media. I also want to make it clear that my paper does not, in any way, intend to discount the profession of an art curator, especially the works of Hans Ulrich Obrist and Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev or the likes of Roberto Chabet and Patrick Flores, who are recognized as some of the most influential personalities in the local art scene. Instead, I aim to illustrate how the fundamental concepts of “arranging and editing of things”

Caring in Curating:

Curating Art, Spaces, and the Self Read More »