This paper is a collection of my experiences as a lecturer-facilitator for the Philippine Cultural Education Program (PCEP) of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA). I was tasked to teach Media-based Cultural Documentation in many parts of the archipelago, spanning seven summers from 2016 to 2023. Many of the experiences describe the various kinds of interaction among the student-scholars, most of whom are Department of Education (DepEd) K-12 teachers. These interactions are byproducts of the numerous pedagogical innovations I took risks to apply to make the learning experiences more dynamic. Looking back, I realize most of these innovations are quite unorthodox, yet they yield reactions and outcomes that are quite surprisingly positive and spontaneous. This created a dynamic that produced quality outputs that enjoy citations up to this day. Thus, I am humbled and excited to share these teachings and lifelong learning experiences with interested readers of this narrative – in the hope that future teachers, mentors, and practitioners may benefit from them.

To illustrate these pedagogies, I will focus particularly on the journey of documenting cultural treasures using the available multimedia technology.

This is my (multimedia) story.

Having been assigned to various parts of the country to spread a deeper appreciation and love for our own rich cultural heritage, I have noticed that the common denominator among all these engagements is that every class starts with palpable enthusiasm and ends with a contagious sense of duty. No matter how strong the regional flavor of a class makeup was, there was always a collective sense of nationalism.

My story also navigates not only pedagogical approaches that I have applied as I saw fit but also includes concrete self-assessment and realization. It shall also include recommendations based on success stories (and, at times, failures) and how I foresee the role of educators of this specific content in the so-called “new normal” and beyond COVID-19.

I purposely divided the narrative by subheadings not just to compartmentalize my flow of thoughts but also to emphasize the specific relevant learnings and realization at hand.

Media-based Cultural Documentation: An Overview and a Journey

Teaching cultural documentation as coursework is almost second nature to me. I have been dabbling in media productions for as long as I can remember, ranging from being a performer to being a heavily invested impresario. I had the good fortune of directing an award-winning video in the 1990s and have since directed live and recorded stage performances. Appearing in a television magazine show and interacting with stalwarts in various creative industries have exposed me to how powerful mass media could be in Filipino society. But what makes this teaching assignment challenging to me is how to channel my students’ familiarity with the many forms of media into a burning desire to use them to produce documentation that is both relevant and inspiring. Once this challenge is hurdled, the love affair with cultural documentation begins.

This is why I believe everything should start with what human nature dictates. Human beings are social creatures. Humans make stories about life and themselves. I sincerely believe that everyone loves to hear stories. And, most certainly, we Filipinos have lots of stories to say and hear. Also, it is always a good place to start our personal stories. Imagine starting an intellectual discourse with stories that we are most familiar with, stories that we heard in both our childhood and adulthood and effortlessly told everyone who wishes to hear them. Facing a class of about 30 people assures me of 30 stories. Thirty new stories, thirty day-to-day scenarios, thirty aspirations, and frustrations. A fantastic playground for facilitators of this pursuit.

This is how I designed CulEd 207 to start. We begin with a story we live to tell. Then, we choose the one that stands out among many others that we are excited to share with the rest of the world.

Urgency

I always begin serious discussions by raising the need to preserve our cultural heritage by focusing on the vanishing aspects of our local milieu. As I adhere to a reflective style of pedagogy, I encourage my scholars to think and reflect on their own way of life, background, and circumstances. The more parochial the story is, the more intimate. A sense of ownership further develops in them, which drives them to express their authentic narrative.

Soon, they realize that as time passes and technology improves, cultural treasures will vanish and, in most cases, be completely forgotten.

I remember coining the term “cultural warriors” in my early days as a lecturer in various speaking engagements all over the country and was pleasantly surprised that many colleagues and advocates of culture have also coined this term to their full advantage. Since then, we have seen “cultural warriors” prompting a battle cry inside and outside the classrooms and lecture halls. In this course work, each scholar is a cultural warrior with one issue, topic, or agenda that strikes a chord in their hearts with urgency.

A Six-Day Workshop Using Both Reflective and Integrative Pedagogies

With this burning desire in mind, documenting vanishing artifacts, practices, traditions, beliefs, or tangible cultural treasures becomes paramount to every scholar who undergoes this course. Each scholar is given the opportunity to collaborate with fellow scholars to create an output that expresses their goals and aspirations.

Given this documentation, course work and other courses in the program follow a one-full-week timetable; previous facilitators have designed to spread the weekdays into milestone accomplishments to ensure an effective learning curve, building the necessary skills to produce the required final output, and most importantly, to develop a deeper sense of purpose. This is how the days in the pursuit of media-based cultural documentation unfold.

Allow me to tag you along with my journey through the following six days.

Day One: Getting the Engines Started

I consider it an asset that we always start the class with a special interest. No one comes to day one with no expectations. Everyone looks forward to a new learning experience. And the pressure for me has always been not to disappoint. However, presenting the main content is not enough. As an educator, I aim to make each student listen and learn, think, rethink, and ultimately ask questions. Questions as basic as “Why are we doing this in the first place?” I have always believed in that age-old saying that “Curiosity is the mother of motivation.”

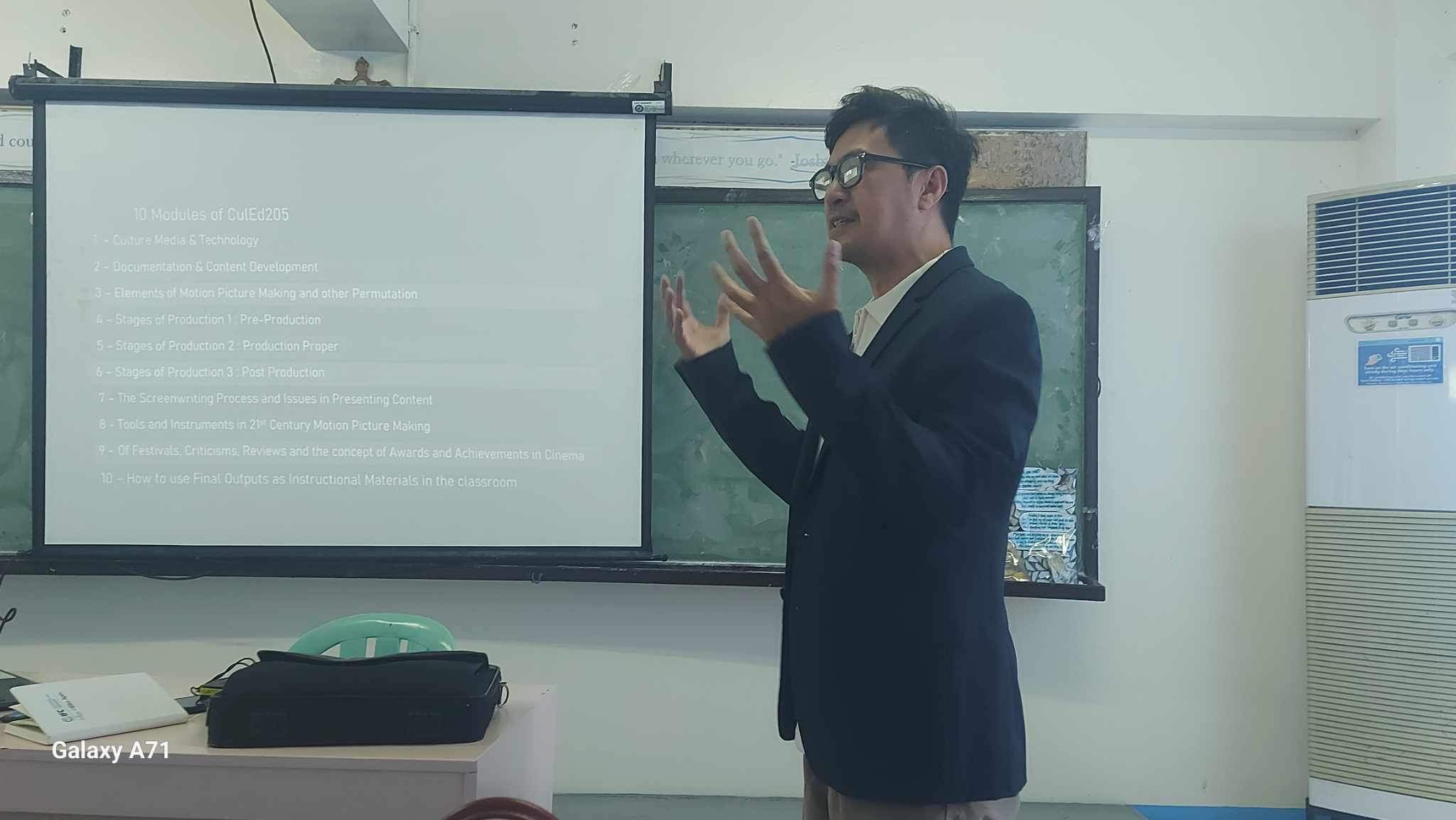

Just like what any syllabus may dictate, the first day of classes will always be an introduction to the content. Like any teacher, I spell out an approved syllabus and then expound on specific learning outcomes, and if a facilitator is well prepared enough, he sets his classroom decorum and expectations with ease.

Engaging scholars in the world of media – specifically popular media – is not difficult. We all live with many different forms of media – from our radios to television, cinema, and now, streaming. Making them understand how we can use the tools of these forms of media to preserve a cultural treasure is an easy task – any passionate facilitator can do that. But it is making them realize the impact of media on society, which is another story. My approach in conducting this lesson is to empower them to think they can use any medium to promote their goals and agenda. In essence, as a facilitator, I allow them to rethink what they themselves could do if they had the power. The power to tell stories.

The content I am talking about is not just my syllabus but students themselves. So, I began the class by asking them to introduce themselves by sharing their stories. Stories of their life. This method not only breaks the ice on the first day but also provides a golden opportunity to creatively insert parts of the content of the lessons as I progress with the ice-breaking activity.

Call it more like a television talk show format where the host, like Boy Abunda or Oprah Winfrey, would talk to each participant. Since most of my students come from very different places from where I came from, engaging with their stories was my means of embracing their energies and local vibes. This method proves effective as they see me more like a party host than a lecturer. I instantly become more of a collaborator to work with and an ally in our common pursuit. With this newly found relationship, I am blessed to witness beautiful stories of life, families, struggles and frustrations, and pride in their cultural heritage.

As the day progresses with conversations about culture, media, and technology and how these three intersect with each other over the years, we, as human beings, are witnesses to the ever-changing and evolving cultural landscape of our homeland. Thus, there is an urgent need to preserve this landscape so that future generations will be aware of it and enjoy and embrace it. Hence, the desire to “document” is born.

In my class, “sharing” is my term for recitation. “Stories” is my term for lessons. And “documentation” is my term for “output.”

The cultural warrior begins his battle.

Day Two: The Pre-Prod

This day is the embodiment of the saying: Walk the Talk! Starting this day is like bringing the entire class to an imaginary Production House town hall meeting. I always tell the scholars to imagine being crew members of GMA 7’s Jessica Soho TV program, and they are tasked to roll down the stories to broadcast for the entire nation to watch. Isn’t that so empowering?

Brainstorming is key. It begins with a topic of choice for each member. Each becomes a storyteller sharing their backgrounds, day-to-day lives, scenarios, and milieu. Then, they agree to choose one that speaks volumes of urgency and relevance.

Equipped with minimal guidance on the basic dos and don’ts in production work, every scholar feels the excitement of a very important task. A burden to carry on their shoulders, a sense of pleasant duty to participate.

Documentaries are produced by corporate media giants such as ABS-CBN or CNN, but through this method, NCCA scholars can produce the same authentic content in just one full day.

By the day’s end, not only has each group drafted a working script for the actual shoot, but it also has achieved what could be an unthinkable accomplishment – to successfully assign roles and responsibilities to each member based on their respective skills, strengths, or resources.

This is indeed integrative pedagogy in action.

Day Three: There Is No Business Like Showbusiness

The most fun part of the entire coursework experience is getting your feet wet. Everyone becomes an actor/actress, a director, a cameraman, a soundman, a costume designer, a makeup artist, a lighting man, or even a production manager. With little to no experience, scholars can transform into these important characters to execute their roles in producing a documentary. Considering that time is limited, one day is usually allotted to shoot all sequences required to complete the work. Marching orders are to produce a documentary feature with a running time of not less than five minutes and not more than fifteen. However, some production work often exceeds this limit due to the richness of the content. As excitement and interest built up during the brainstorming, I witnessed how various groups have taken great lengths to achieve their ideal documentation.

In my Baguio city class in 2016, a group of scholars decided to return to their hometown, which took them almost twenty hours round trip by bus. These students insisted that to make the documentation authentic, they needed to return to where the story originated. They documented a peculiar type of rich cake famous in a remote village in Kalinga.

In some cases, certain groups are blessed with serendipity. In Calbayog, one group had a great fortune and good timing to document an ongoing fiesta three towns away. In Vigan, one group dared to explore a village in the northern part of the province to investigate an alleged peculiar practice of eating cats as a delicacy. However, after encountering potentially hostile resource people, they opted for a less controversial topic about making local sweets called Tira Tira.

In my Cagayan De Oro stint in 2017, a group decided to do a quick roundtrip to the Agusan River to document the floating houses while the river had not totally dried up in the middle of summer – a feat that is remarkable considering none of them had an architectural background.

In Marinduque, a group of young teachers took on an adventure to go into a remote part of the island to document an abandoned Spanish period fortress, which locals fondly call Baluwarte. A site that not many locals even know existed.

These are just a few of the dozens of exploits I have witnessed as a facilitator that I now consider treasures as they are testaments of how rich and diverse our culture is.

All magnificent images, all beautiful stories told. Forever documented and captured on video.

Day Four: The Post-Prod

Not everyone is cut out for post-production work – such as video and audio editing. I don’t even espouse to teach them this. This is not part of my pedagogical approach. This is not a mass communication course nor a multimedia class. But what I warned them against is that this part of the production work is more laborious than the actual shoot. I presented them with alternatives, considering no one in the class was professionally trained to do post-prod work. There is always an easy way of handling this part of the job.

I did tap into everyone’s proclivity to use everyday gadgets such as smartphones, laptops, or DSLR cameras. For those who are brave and techie enough, I informed them of the growing number of apps that make editing work a piece of cake -if one is just willing to learn. Based on my personal experiences over the past five years, hardly anyone volunteered to learn this app in such a short amount of time.

Fortunately, I have devised a group member selection system that enables every group to have someone tech-savvy enough to assume the role of editor. I found out much later that this led to many more scholars wanting to learn a new skill because of their exposure to this process if only more time and specialized training were offered. After a thorough and tiring day, only those who have the energy to continue a tech-heavy day have little participation in the actual shoot. Editors are already pre-selected, pre-anointed, and pre-assigned with this burden, so much so that they were not required to attend the shoot.

A clear division of labor comes naturally after the marching orders are given. Treating the expected output organically without any rigid, corporate-style expectation-setting instructions gives the group a sense of flexibility and freedom in executing their creative ideas.

I remember in one of the classes I conducted in 2023, one of the scholars, who I assume to be already in her 40s, asked me if she could ask her son, who I learned to be an award-winning student filmmaker, to help her with the documentary. “Absolutely!” I told her.

Allowing others to help, especially those with special technical skills, flows naturally if one is impassioned to produce significant output. Sometimes, frustrations and desperation trigger us to be intuitive problem solvers. It does not matter if one belonged to Generation X or if someone has absolutely had zero to limited digital know-how; I still made it clear that everyone can produce their own stories to tell the world. Today, one does not need high-tech equipment to produce a motion picture. Smartphones are enough.

Day Five: The Public Screening

The film festival begins.

All documentations are presented, viewed, and critiqued. And the best part is that the whole proceeding is open to the public. I encouraged each scholar to bring in friends, family, or people who have been part of their documentary.

In some universities, we use their auditoriums; in others, we just use a makeshift covered court for this activity. However, the audio-visual equipment set up is, the public viewing remains one of the most gratifying moments of my teaching life – seeing all the outputs unfold.

This is how it happens. Each group is allowed to introduce themselves and their roles before screening their documentary video. A short introduction to the material is required. The appointed director usually assumes this responsibility. After viewing, the entire cast and crew are again asked to go on stage, like in any film festival, and given the proper recognition they deserve.

Sometimes, a Q and A happens, especially when guests are present. Conversations arise when scholars explore how their materials could be used as instructional aides. Others are inspired to recommend a regular documentation effort in their respective schools with the proper budget and support.

The experience brings limitless potential in collaboration with other interested groups with similar advocacies. However, to me, the most noteworthy effect of this festival is the desire to bring this learning experience down to the level of their constituents. I sincerely believe today’s younger generation is even more technically equipped to take on this endeavor of documenting through recorded motion pictures if only given the opportunity and support.

Day Six: And the best picture goes to…

And what better way to encapsulate a week-long learning experience and hard work than to reward everyone with proper and well-deserved recognition?

For most of the end-of-the-week culmination activities I have conducted for CulEd 207, the last day always becomes like a “festival.” Every single day of the course was geared towards this fiesta-like activity. It feels almost like a mandatory component of the course – a celebration after the end of a productive week.

Instead of grades, I give awards in a manner similar to award shows like the Oscars. Sometimes, when the opportunity arises, we invite critics to share their thoughts a-la-Manunuri. This assessment method is more open and spontaneous and seems accepted by most of my students. Constructive criticisms are treated like badges of accomplishment and honor for completing their goals.

A rubric may be drafted to help them understand how they are being assessed in every specific aspect of their documentation, but overall, the public and collective recognition of one’s work is enough to give each scholar a sense of accomplishment.

The fun part will always be when simulating an awards night ceremony, and I encourage every participant to dress up their best as if they are all celebrities. I want them to be proud of their accomplishments – as legitimate creators of documentary features. A feat that has been accomplished in so short a time with the crudest technical equipment accessible to them. At the end of the day, I always emphasize that the story’s authenticity is more important than glaring technical superiority.

Everyone goes home smiling, with a deeper sense of commitment to use what they have learned in spreading awareness and love of our culture to their own respective spheres of influence.

And for me, it is a case of a mission accomplished – and with a smile.

Cultural Documentation in the Time of COVID

As early as mid-March 2020, we at PCEP were at a crossroads to either continue or cancel the delivery of Media-based Cultural Documentation to the scholars of De La Salle University in Ozamis. There were doubts about whether the learning outcome would be achieved despite no face-to-face interaction. Much worry was felt about how, on a lockdown, a group could collaborate and execute production work peculiar to media-based cultural documentation output.

Even as early as January, I had already received my teaching load and was excited to immerse myself in another local culture. However, due to the pandemic, almost all plans had to be put on hold – this engagement included.

However, as weeks passed and coping mechanisms were shared by people in various respective industries, decision-makers in the NCCA and host De La Salle University Ozamis have agreed to proceed with CulEd 207 using available telecommunication and online platforms.

So, on April 27th of 2020, I formally opened my CulEd class with 30 plus scholars based mostly in Ozamis and nearby cities. And yes, it was fully online. My first choice of platform is Facebook Live. We initially agreed to follow the conventional timetable of five to six daily sessions spread across one week. Because it was still early in the pandemic months, there were not many alternative options to use. Zoom was not yet fully secure. Google Classroom has not been introduced. Microsoft Teams was not free. So, Facebook was not only the most accessible, but it was also, by default, the only social media platform common to all scholars.

What transpired in this new experience is worth another story to tell. Imagine the tremendous effort on my part to get the content and learning outcomes across by talking to a computer monitor. Most old-school instructors would abhor the fact that you directly talk to a machine instead of warm and lively bodies. Scholars faced many challenges on their side in this new relationship. Intermittent and unreliable interconnectivity hampers their learning experiences. I clearly recall that one of the scholars had to excuse herself because she could not travel to a spot outside her house to catch a signal because of the lockdown.

As part of my adjustment as a facilitator, a method I used in relaying the lessons and explaining the required activity to my online scholars (in a lockdown) is relating every part of the syllabus to how it was conducted in the past in a traditional face-to-face setup. Then, I challenged them to think creatively about how best to conduct the activities given their own limitation. I certainly did not have the answers then and had to fish for ideas as we progressed. At that point, I think it was important to establish ways and means to allow the scholars to better appreciate the content and process. These are still as relevant and relatable as the traditional way of delivery in the past, even though we need to embrace changes due to this pandemic.

The biggest difference from how I conducted this summer is that all production phases (pre-, actual, and post-prod) must be stretched from one day to a week for each phase. Lecture hours are limited because of internet hours available, and class interaction is almost negligible. Synchronous sessions were limited to the delivery of instructions and quick updates. This timetable adjustment also meant that their final documentary could be submitted a month later.

While we were treading on new grounds, the adjustment we made proved to be successful. The equivalence of Days 5 and 6 of my conventional delivery was a Zoom meeting where each scholar/viewer shared the screen to play their documentaries – very much like a streaming service in the comforts of your own desks at home. What was absent was the celebratory moments, something that we will need to put on hold until mass gatherings are allowed again.

Speaking to scholars and getting their feedback revealed just as what I have observed with my previous face-to-face sessions from previous years, this batch has also expressed their strong sense of duty to continue preserving our cultural treasures through documentaries that are accessible to everyone.

Conversion Into Modules and Online Interaction

Realizing that COVID-19 was here to stay for an uncertain amount of time, there was a need to convert the entire program into blended or fully online delivery. Not all host universities may have the proper Learning Management Systems to support the program, so using alternative media platforms is either expensive to acquire or too inaccessible.

There was a call to reconfigure or recalibrate course content and delivery to make the program more efficient in the new normal. This involved a comprehensive review of the syllabi, resulting in full conversion into palatable modules. Cultural documentation was no exception.

As mentioned, I have successfully facilitated the course online from April to May 2020. Although the learning outcomes are pretty much unchanged, the delivery has been quite challenging. Many platforms were available, but it was not easy to choose one that everyone could easily embrace. By default, Facebook was and has always been the most preferred by all – until Zoom became more accessible.

What did I see next?

Looking back, this was what I saw next. As living our day-to-day life with the COVID-19 scenario was getting clearer by the day, one thing was now most certain: traditional class setup and teaching methods would be a thing of the past – especially for cultural documentation. Video and audio recording equipment improves quality and becomes more affordable; administering information will no longer be shaped by time factors or physical space. Sister Felicitas of St. Paul University College of Education once said that teachers are no longer needed in the classroom if their prime role is just to administer content. Yes, teachers can vanish in the classroom landscape if we only focus on knowledge-based learning. Students can get that from Google. However, what I espouse is that we focus on both critical thinking and skills-building pedagogies.

We have witnessed that even on the 2021 Emmy Awards night, the celebration was conducted fully online. Technology has taken over. Entertainment was still delivered without mass gatherings. Even without mass gatherings, viewing content will still be accessible through streaming and other social media platforms.

What does this prove? It only means to say that the way to survive is to be friends with technology. And in the world of education, technology should be used to advance and support new pedagogical models.

This coursework can still be conducted online, as successfully proven by the positive collective experiences of the scholars from Ozamiz. In a class of 36, they produced ten amazing documentaries that are now part of NCCA- PCEP’s rich archive of cultural documentary shorts either on cloud, website, or traditional hardware such as DVD, USB, or VCDs. These materials are potential instructional materials that are accessible not just for blended learning but also for fully online delivery.

And what do I see in the future for this cultural documentation coursework? I foresee a Netflix-type streaming service where all our documentary outputs are stored and viewed not only as a repository of cultural treasures but also as a depot of instructional materials that are easily accessible – whether there is a pandemic or not. An online and universal testament to our cultural warrior’s dedication to preserve our rich culture and of how we perpetually attune ourselves to the improvements in our technology in media. Every participant who goes through media-based cultural documentation should aspire to contribute to a content library. Content that is fully accessible, usable for instructional purposes, and downloadable to spark conversation and cultural discourses.

So, this was my story – pre-pandemic and at the height of it. It is still unfolding and evolving as we speak. I am eager to see what technologies in media may come our way soon. But there is one thing that remains in my heart – it is that sense of duty to pass on to the generations to come, and there is an urgent need to document our rich cultural heritage before they vanish and be forgotten forever.

I end this personal narrative by addressing my colleagues in this endeavor by asking:

“This has been my story; now begin yours!”

The end.

Postscript

Fast forward to 2024. This may be somewhat of a rehashed narrative written for a new audience post-pandemic. It would be interesting to note that despite the evolution of more sophisticated technology in media in the past several years, the heart and soul of cultural documentation remain. Time only makes our cultural treasures richer as they vanish even more quickly. Levels of interest in preserving our culture may differ, but there is no denying that cultural heritage will always be a viable content – for as long as we, as human beings, can still listen to a story.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Jose Manuel V. Garcia is a licensed architect by profession, a design and multi-media arts educator by vocation, and a creative impresario by diversion. He is the Campus Architect and Director of the General Education Program at NU-Asia Pacific College. He holds a BS in Architecture from the University of the Philippines Diliman and an MA in Educational Leadership from St. Paul’s University Manila. (Corresponding author: manoletg@apc.edu.ph)